PEACH Program Provides Compassionate Palliative Care for City’s Homeless

Image: “Toronto Street Sleeper” by Andy Burgess / CC 2.0

On any given night, over 30,000 people are homeless in Canada with 2,880 unsheltered outside in cars, parks or on the street, 14,400 staying in emergency shelters, 7,350 staying in shelters for violence against women, and 4,464 people in temporary institutional accommodations such as hospitals, prisons or interim housing.1 Each year, approximately 200,000 people experience homelessness in Canada, and some data suggest that close to 1.3 million people have experienced homelessness at some point in the last five years.1

Housing is a human right, as well as an important social determinant of health. It has been shown that in Toronto homeless people are twice as likely to report having diabetes, 4 times as likely to have cancer, 5 times as likely to have heart disease, and 29 times as likely to hepatitis C, when compared to the general population.2 Life expectancies for the homeless are also much lower, estimated to be between 34 and 47 years*.2 Homelessness also creates a large societal economic burden, currently costing our economy $7 billion dollars every year.1

In response to these sobering statistics, a coalition of advocates, health care providers and community groups have mobilized to increase awareness of the national impact of homelessness and to demand policy solutions, including a national housing strategy. So far there has been growing awareness of the issues surrounding homelessness in the public eye, but there has been limited policy movement and action by politicians. For example, in 2012, Bill C-400, ‘An Act to ensure secure, adequate, accessible and affordable housing for Canadians,’ was introduced as a private member’s bill in the House of Commons by NDP Member of Parliament Marie-Claude Marin. Its aim was to provide key recommendations about housing within a human rights framework*.3 However, the bill unceremoniously failed to pass the second reading by a vote of 153 to 129 on February 27, 2013.3

A parallel issue that has slowly been gaining traction in Canadian health policy circles is palliative care. Recently, Minister of Health Rona Ambrose highlighted the need for high quality palliative care as a component of end of life care for the growing elderly population in Canada.4 Generally, Canadian palliative care programs are designed with the mainstream population in mind. Although there have been some efforts to accommodate the needs of other groups, existing programs typically do not serve the needs of marginalized populations such as the homeless and the vulnerably housed – groups perhaps the most in need of care. Studies show that over 50% of Toronto’s homeless population don’t have access to a family physician, and that many die without access to health care providers trained in end of life care1.

Given the complexity of homelessness in Canada, a new program is seeking to improve access to and quality of end of life care for the homeless. Palliative Education and Care for the Homeless, or PEACH is a mobile, shelter-based consultation, support and education program designed to provide early palliative care for vulnerably housed and homeless individuals in Toronto. PEACH operates out of Inner City Health Associates, which works in over 40 shelters and community sites across the city and supports primary care physicians and other healthcare providers in identifying early palliative care needs for the homeless. Naheed Dosani, a palliative care physician working with Inner City Health Associates and the PEACH program, explains their strategy, “What we are doing with PEACH is […] taking inner city health services and linking [them] with the latest thinking in palliative care, which is early palliative care, and we’re trying to mesh the two. We are applying this knowledge […] to the needs of a vulnerable homeless population, which to our knowledge has never been done before”. Key to the PEACH model has been its focus on promoting and protecting the dignity and care goals of patients’ within a shared decision making process. Discussing the potential impacts of PEACH, Dosani says: “Several studies have noted the benefits [that] early speciality palliative care can have – for example, they have been shown to lead to improvement in mood and function*, reduced symptoms [and] reduced caregiver burn-out, and some studies have even shown that early palliative care can actually prolong […] life.”7

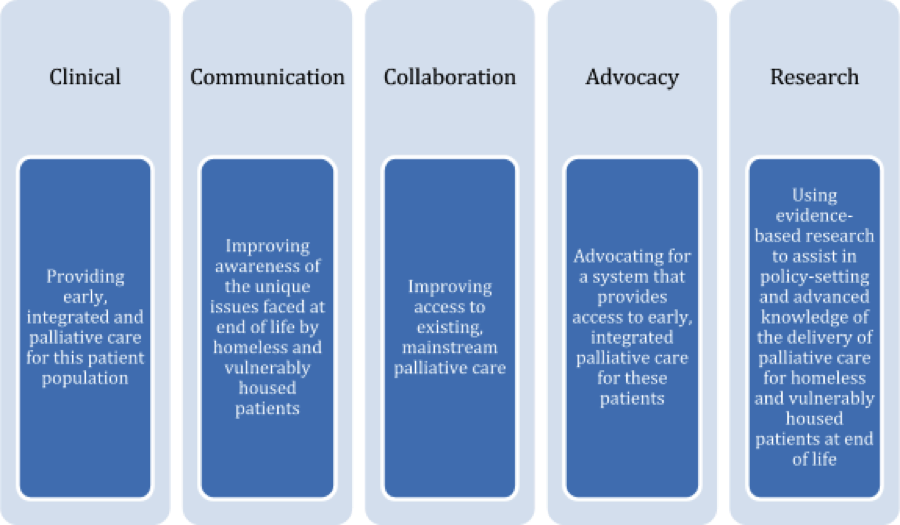

Five principles of the PEACH program

Dosani says, “We work as a team and we work to support. The E is before the C for reason in PEACH. We’re really about education and awareness. We realize that, as a palliative care program, we are not going to be able to reach all of the palliative care needs of the homeless. However, what we aim to do is increase awareness, advance practice and potentially add to the body knowledge that currently exists about this population as they approach end of life.”

What has been especially promising about the PEACH program is its commitment to providing its clients with the full spectrum of care, regardless of their location or disease trajectory. In relation to this goal, PEACH is expanding the context of palliative care from a solely hospital-based model to one that includes shelters. Often, people wish to receive end of life care in a familiar, comfortable environment.6 When providing patient-centered care to people who are homeless and vulnerably housed, addressing patient priorities with respect to how, when and where care is delivered is a particularly important and complicated consideration. To make this more possible, PEACH has developed partnerships with various palliative care centres across the city. Partners include the Temmy Latner Center for Palliative Care, the Kensington Hospice, the St. Michael’s Palliative Care Unit, Toronto Grace Centre and the Toronto Central Community Care Access Centre (CCAC).

Another crucial aspect of PEACH’s approach is the interdisciplinary and collaborative way in which it delivers palliative care. Dosani explains, “I work alongside my teammate, Namrig Ahmed, an amazing RN, who works with me on the front lines, seeing patients. We do consults together. We are delivering palliative care the way it should [be delivered], in the best possible way, which is in an interdisciplinary fashion.” This inderdisciplinarity is an advantage in addressing the many institutional and systemic barriers that the homeless face when accessing health care services, especially palliative care. A recent study highlighted several key factors that must be addressed to increase access and better serve homeless patients who are terminally ill. These include improving interactions between the health care system and homeless individuals, training healthcare providers in how to treat homeless people with compassion and dignity, delivering patient-centered care, and ensuring that there are alternative models of health care delivery to better cater to the unique needs of the homeless population.4 PEACH has been actively addressing these issues in its program.

PEACH has also been paving the way toward improving the lives of homeless and vulnerably housed individuals while keeping the values of social justice, equity and compassion close in mind*. Dosani remarks that “Global health happens all around the world, and programs like PEACH are an interesting example of the principles of global health being applied to a local context.” PEACH is starting to tackle the institutional and systemic barriers to access and quality of palliative care for this patient population. This is an important health equity issue, because, as Dr. Dosani eloquently puts it, “Palliative care is not about dying, it’s about living well, and living well with dignity, and this is still very true for homeless and vulnerably housed populations.”

Canada is the only G8 country without a national housing strategy, which is surprising for a nation that is so wealthy and that has declared a commitment to protecting and respecting human rights. There is increasing discussion in federal policy circles about palliative care and homelessness, and it is the hope of many advocates that such discussions also focus on the intersection of these two very important issues. It is important to respect and protect the right to housing, health and health care for all people – especially vulnerable populations – and the least we can do in our society is to ensure that this right is protected not only during life but at the end of life as well.

To learn more about PEACH, please write to peach@smh.ca and check out http://www.icha-toronto.ca/sites/peach. You can follow Naheed Dosani on Twitter at @NaheedD.

References

Street Health. (2007). The 2007 Street Health Report. Retrieved from http://www.streethealth.ca/downloads/the-street-health-report-2007.pdf

Gaetz, S., Donaldson, J., Richter, T., & Gulliver, T. (2013). The State of Homelessness in Canada 2013 – Homeless Hub Paper # 4. Retrieved from http://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/SOHC2103.pdf

Bill C-400: An Act to ensure secure, adequate, accessible and affordable housing for Canadians. 1st Feb. 16, 2012. 41st Parliament. 1st Session. Retrieved from http://openparliament.ca/bills/41-1/C-400/

Lunn, S. (2014, September 15). Rona Ambrose says Canada needs better palliative care. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/rona-ambrose-says-canada-needs-better-palliative-care-1.2764813

Koehler, G. (2014, July 29). Palliative care for the homeless. St. Michael’s Hospital Newsroom. Retrieved from http://www.stmichaelshospital.com/media/detail.php?source=hospital_news/2014/20140805a_hn

Krakowsky, Y., Gofine, M., Brown, P., Danizer, J., & Knowles, H. (2012). Increasing Access – A Qualitative Study of Homelessness and Palliative Care in a Major Urban Center. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, 30(3), 268-270.

Temel, J.S., Greer, J.A., Muzikansky, A., Gallagher, E.R., Admane, S., Jackson, V.A., et al. (2010). Early palliative care for Patients with Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 363, 733-742.