A Deadly Combination: Conflict, Climate Change, and Covid-19 in Aden, Yemen

Original Illustration by Cassandra Seal

“I never expected to see what is happening right now, here in Aden. The situation is insane. People are falling down, one by one, like dominoes.”

Dr. Ammar Derwish describes the harrowing situation in Aden, Yemen as COVID-19 spread in the city[1].

In the months of April and May 2020 in Aden, residents of this interim capital city in south Yemen suffered from multiple waves of conflict, floods, COVID-19 infections, and other diseases such as dengue and chikungunya. The internationally recognized Yemeni government declared the city as a “disaster zone” and an “infected city,” only a few weeks after the first two COVD-19 attributed deaths were reported[2,3]. The compounding combination of armed conflict, floods, and widespread transmission of infectious diseases proved to be deadly. News agencies, international aid organizations, and Adeni residents on social media platforms raised alarms on an unprecedented increase in burials, one of the only indicators to assess the impact of this triple threat[4,5]. The true death toll still remains unknown. However, burial statistics showed that there were 80 deaths per day in mid-May alone, which is astounding when compared to the average figure of 10 deaths per day during the same period in years prior[4].

(Image:UNOCHA[6])

This tragic disaster was a result of many colliding issues. The public health response was limited as a result of the ongoing armed conflict, the economic and travel blockade imposed by the Saudi-led coalition, and fractured governance highly dependent on international humanitarian aid[7]. Furthermore, global health inequities have left low-income countries, such as Yemen, behind in the race to access COVID-19 diagnostic tools, personal protective equipment (PPE), treatments, and vaccinations[8].

As one of the worst complex humanitarian emergencies today, the conflict in Yemen has created extremely difficult conditions for public and global health responses. The events that transpired from April to May 2020 in Aden are complex and multifaceted. Solving this crisis will require not only an immediate end to the conflict, but also for Yemen to contend with the impact of climate change and the burden of infectious disease on its healthcare system.

Setting the scene

Following the 2014 violent coup by the Houthi movement in Yemen’s capital city, Sana’a, the internationally recognized Saudi-backed government led by Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi fled to Riyadh and declared the southern city of Aden as the interim capital city. Until this day, the Houthis continue to control the northern regions of Yemen, while the internationally recognized Yemeni government operates out of the city of Aden. Further complicating the warfront in the southern region is the separatist movement backed by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), known as the Southern Transitional Council, which stood in opposition to the Hadi’s regime and the Houthi movement[9].

The conflict between these warring parties has devastated vital civilian infrastructure throughout the country, including indiscriminate attacks on health facilities leading to the significant deterioration in the healthcare system[10]. Essential services and institutions have been further weakened by the sea, land, and air blockade imposed by the Saudi Arabian-led coalition, which has restricted the import of essential goods such as food, medicine, and fuel[11].

Only half of all healthcare facilities are currently operating. Water infrastructure is operating at less than 5% efficiency and 90% of the population lacks access to publicly provided electricity[7]. Approximately 20.7 million, or more than 66% of the population, requires humanitarian assistance[7]. The United Nation (UN) estimates that over 130,000 deaths during the conflict were due to indirect causes resulting from war-induced disruptions, such as food shortages, limited access to healthcare and social services, and economic collapse [12].

As a result of these factors, the country is highly dependent on international aid. In regions under the control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government, the health response is formally led by the Ministry of Public Health and Population in partnership with the UN Office of the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) and other international non-governmental organizations (INGOs).

Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) and other international non-governmental organizations (INGOs).

The floods

Climate induced shocks such as flash floods, droughts, and unprecedented cyclones have become more and more common over the years in Yemen[13,14]. The vulnerability of the country to these changing weather patterns was evident in 2020 when the atypical tropical storms in this arid region proved to be disastrous. The floods began in mid-March, where heavy rains triggered a major flash flood, killing two people in Aden[15]. Doctors warned that action must be taken by the government to resolve the issue of stagnant water that results in a large number of vector-mediated infections such as dengue, chikungunya, malaria, and cholera[16].

On April 10th, the first case of COVID-19 was detected in the port of Shihr, which lies 540 km east of Aden, and many feared that the simultaneous spread of water-borne infectious diseases alongside an outbreak of COVID-19 would surmount to a catastrophe[17].

A more devastating flood followed on April 21 with more significant damage. At least 10 fatalities were reported and around 30 people were injured as the streets turned to rivers[15]. Buildings, homes, and infrastructure were destroyed, and water supplies were polluted[6,18]. The Ministry of Electricity reported a total power outage in Aden, disrupting drinking water pumps and communications in the entire city. Thousands of people were unable to access basic food, shelter, and healthcare services. Shortly after, on April 22nd, the Yemeni authorities declared Aden an “area of disaster” due to the damages, all the while the looming threat of water-borne diseases and COVID-19 lingered [18].

Undoubtedly, the country was ill-equipped to cope with the floods. With political fragmentation, lack of funding, and non-payment of public salaries, the response to the floods was insufficient. Additionally, the international humanitarian response led by UNOCHA has been critiqued for its ill-informed, overly bureaucratic, and weak strategy that is focused on implementing their own agenda through temporary, short-term projects aimed to satisfy donors [19]. Other critiques include a neglect to fund long-term solutions needed to tackle Yemen’s vulnerability to climate change and a lack of sufficient inclusion of Yemeni professionals [14, 19].

Clashes in the city

Shortly after the disastrous flooding on April 25th, 2020, the Southern Transitional Council declared self-rule of Aden and armed clashes broke out between pro-Hadi government troops and the separatist party. An additional 10 fatalities were recorded that week, and these clashes limited the movement of people, goods, and essential services at a very critical time in the city[20]. With fractured governance of the city came a fractured response to the public health crisis that followed the flooding and violent clashes.

An “infected” city

On April 30, 2020, Yemen recorded its first two deaths linked with COVID-19 symptoms in Aden, with five confirmed cases of COVID-19[17]. At the same time, the flooded streets of Aden, riddled with garbage due to inoperative waste management services, became breeding grounds for mosquitos. As doctors had forewarned, hospitals noted hundreds to thousands of patients suffering from viral fevers due to vector-mediated infections including malaria, dengue, and chikungunya[21,22]. This marked the beginning of a deadly period for Aden as the burden of these diseases weighed heavily on an already stretched fragile healthcare system.

Several hospitals shut down due to limited beds, oxygen, equipment, and workforce as healthcare workers were afraid of contracting COVID-19 due to the lack of basic equipment, protective gear, and critical health supplies for outbreak management[23]. With an already diminished healthcare workforce who experienced multiple cuts to their salaries over the course of the war, having access to protective equipment was essential to prevent deaths among these workers[24]. As of July 2020, 97 health workers reportedly died from COVID-19 infections[25].

In an old, refurbished cancer hospital, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) set up the only COVID-19 treatment centre in Aden. This hospital only treated serious cases due to the limited beds and equipment. The other hospitals in Aden could barely keep up with viral disease cases, turning away patients exhibiting COVID-like symptoms. There were not enough ventilators, oxygen concentrators, nor a reliable supply chain of regulators, tubing, masks, and other equipment needed for treating patients[26].

With a shortage of testing kits and other equipment to diagnose viral fevers, it was difficult to know whether someone was infected by COVID-19 or another viral disease[21,27]. Regarding testing capacity for COVID-19, Yemen was entirely dependent on support from the World Health Organization (WHO) for receiving Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) reagents and training laboratory staff in this method. There are only four public health laboratories in Yemen that have the capacity to test for COVID-19 using PCR testing, with only one operating in Aden[28]. Within this resource-limited setting, PCR testing comes with many obstacles: the stability and performance of the temperature sensitive PCR reagents can be compromised by frequent power outages; poor road networks make the timely transportation of samples to the laboratory extremely difficult; and laboratory staff received short and limited training from WHO[28]. Therefore, the official number of COVID-19 infections and attributed deaths are a severe underestimate, even as they place Yemen with the highest fatality rate of 27%, five times the global average[25,29]. Furthermore, there are no estimates for the prevalence and burden of vector-mediated infections to capture the congruent epidemics of dengue, chikungunya, and malaria.

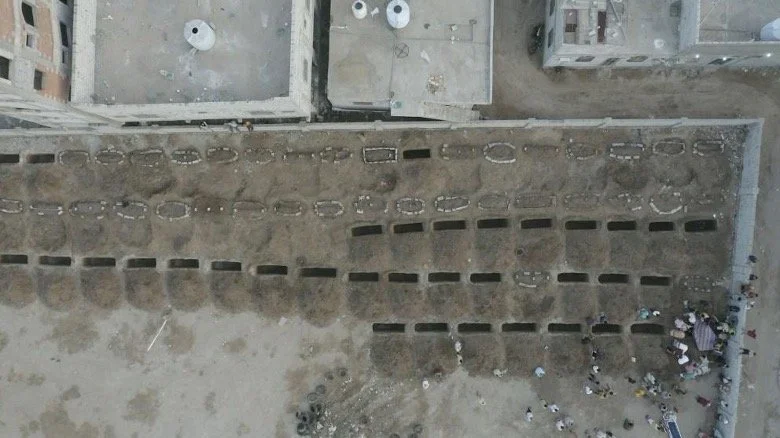

(Image: SkyNews[5])

Drone footage taken by journalists showed rows upon rows of freshly dug graves[5]. From April 30 to May 17, MSF reported a total of 173 patients were admitted and of whom, at least 68 had died[26,27]. According to Save the Children, official counts in Aden report at least 385 deaths of people with COVID-19-like symptoms from May 7 to May 14, a fivefold increase from the week prior[30]. Using records of burial permits in Aden, Dr. Abdualla Bin Gouth estimated 950 deaths in the first two weeks of May. From his study estimating the prevalence of the multiple diseases in the Cuban-Yemeni Hospital, Dr. Gouth found that 16.4% of cases were malaria, 23.3% were dengue, 25% were Chikungunya, 26.6% of cases were respiratory tract infections, and only 8.4% of cases were likely COVID-19[31]. Another study using satellite imagery of cemeteries estimated more than 2,000 excess deaths between April 1 – July 6, 2020[32]. While hospitals closed, doctors like Dr. Ammar Derwish continued to visit patients at their homes, battling the spread of these many diseases in the community with the very limited resources available[1].

Future considerations for Aden’s triple threat

In April and May 2020, residents of Aden faced deadly threats from climate change, conflict, and infectious diseases. This is but one snapshot of the multiple threats and competing public health challenges that continue to occur in this complex humanitarian emergency. To stress, Yemen cannot afford to neglect the impact of climate change, which not only drives the spread of infectious disease, but can also increase tensions between warring parties over resources and land[14]. Without an end to the conflict, Yemenis are caught between the limited response from INGOs and the fractured governance and coordination by local authorities, leaving sustainable and long-term solutions to the public health and climate change crises far and few.

Anwaar Baobeid (she/her), MPH, is an independent global health research and policy consultant. She has conducted and published research on gender equity in global health research publishing with the Centre of Global Health, University of Toronto (UofT). As a settler on so-called Canada, by way of Yemen, her research focuses on the right to health of temporary migrants in Canada as well as the intersections of community health work, climate change, gender equity, and public health in Yemen. Anwaar was awarded the Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Incoming Graduate Scholarship during her Master of Public Health, specializing in Global Health and Development Policy and Power from UofT.

References

Derwish, A. (2020). How coronavirus hit Aden: A Yemeni doctor’s diary. The New Humanitarian. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/special-report/2020/07/07/coronavirus-aden-yemen-doctor-diary

2. Reuters Staff. (2020). Yemen’s emergency coronavirus committee declares Aden an infested city | Reuters. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-yemen-idUSKBN22N06W?taid=5eb8ba20e97cde0001797fe8&utm_campaign=trueAnthem:+Trending+Content&utm_medium=trueAnthem&utm_source=twitter

3. AlJazeera. (2020). Yemen gov’t declares Aden ‘infested’ as coronavirus spreads . AlJazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/5/11/yemen-govt-declares-aden-infested-as-coronavirus-spreads

4. Medecins Sans Frontieres. (2020). Yemen: High number of deaths due to COVID-19 signals wider catastrophe in Aden. MSF News & Stories. https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/latest/yemen-high-number-deaths-due-covid-19-signals-wider-catastrophe-aden

5. Stone, M. (2020). Coronavirus will “delete Yemen from maps all over the world.” Sky News. https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-will-delete-yemen-from-maps-all-over-the-world-11989917

6. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2020). Yemen: Flooding affects thousands. OCHA Media Centre. https://www.unocha.org/story/yemen-flooding-affects-thousands

7. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2021). Yemen Humanitarian Needs Overview 2021 . OCHA. https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-needs-overview-2021-february-2021-enar

8. Tan, M. (2021). COVID-19 in an inequitable world: the last, the lost and the least. International Health, 13(6), 493–496. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihab057

9. Montgomery, M. (2021). A Timeline of the Yemen Crisis, from the 1990s to the Present. Arab Centre Washington DC. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/a-timeline-of-the-yemen-crisis-from-the-1990s-to-the-present

10. Qirbi, N., & Ismail, S. A. (2017). Health system functionality in a low-income country in the midst of conflict: The case of Yemen. Health Policy and Planning, 32(6), 911–922. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx031

11. Human Rights Watch. (2017). Yemen: Coalition Blockade Imperils Civilians. Human Righs Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/12/07/yemen-coalition-blockade-imperils-civilians

12. United Nations. (2020). UN humanitarian office puts Yemen war dead at 233,000, mostly from ‘indirect causes.’ UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/12/1078972

13. Lackner, H., & El-Eryani, A. (2020). Yemen’s Environmental Crisis Is the Biggest Risk for Its Future. The Century Foundation. https://tcf.org/content/report/yemens-environmental-crisis-biggest-risk-future/?session=1&agreed=1

14. al-Mowafak, H. (2021). Yemen’s Forgotten Environmental Crisis Can Further Complicate Peacebuilding Efforts. Yemen Policy Center. https://www.yemenpolicy.org/yemens-forgotten-environmental-crisis-can-further-complicate-peacebuilding-efforts/

15. Floodlist News. (2020). Yemen – More Devastating Flash Floods in Aden After 125mm of Rain. Floodlist News. https://floodlist.com/asia/yemen-floods-aden-april-2020

16. Arab News. (2020). Deadly floods drown pending fears of coronavirus in Yemen’s Aden. Arab News. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1647146/middle-east

17. BBC News. (2020). Coronavirus: Yemen reports first deaths amid fears of undetected spread . BBC News . https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-52485101

18. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2020). Yemen: Flash Floods Flash Update No. 2 (As of 23 April 2020). OCHA. https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-flash-floods-flash-update-no-2-23-april-2020-enar

19. Nasser, A. (2022). The Flaws and Failures of International Humanitarian Aid to Yemen. Arab Centre Washington DC. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-flaws-and-failures-of-international-humanitarian-aid-to-yemen/

20. Ghobari, M., & Mokhashef, M. (2020). Yemen separatists announce self-rule in south, complicating peace efforts. Reuters . https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-south-idUSKCN228003

21. France 24. (2020). Deaths from coronavirus-like symptoms surge in Yemen’s Aden. France 24. https://www.france24.com/en/20200518-deaths-from-coronavirus-like-symptoms-surge-in-yemen-s-aden

22. Al-Batiti, S. (2020). Weakened by war and floods, Yemen fights twin health threat. Thomson Reuters Foundation. https://news.trust.org/item/20200514081825-770qg/

23. Alrubaiee, G. G., Al-Qalah, T. A. H., & Al-Aawar, M. S. A. (2020). Knowledge, attitudes, anxiety, and preventive behaviours towards COVID-19 among health care providers in Yemen: an online cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09644-y

24. Al-Ashwal, F. Y., Kubas, M., Zawiah, M., Bitar, A. N., Mukred Saeed, R., Sulaiman, S. A. S., Khan, A. H., & Ghadzi, S. M. S. (2020). Healthcare workers’ knowledge, preparedness, counselling practices, and perceived barriers to confront COVID-19: A cross-sectional study from a war-torn country, Yemen. PLOS ONE, 15(12), e0243962. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243962

25. MedGlobal. (2020). A Tipping Point for Yemen’s Health System: The Impact of COVID-19 in a Fragile State. https://medglobal.org/yemen-covid-report-july2020/

26. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). (2020). A lot of people die quickly of coronavirus COVID-19 in Yemen. MSF. https://www.msf.org/lot-people-die-quickly-covid-19-yemen

27. Devi, S. (2020). Fears of “highly catastrophic” COVID-19 spread in Yemen. Lancet , 395(10238), 1683. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31235-6

28. Dhabaan, G. N., Al-Soneidar, W. A., & Al-Hebshi, N. N. (2020). Challenges to testing COVID-19 in conflict zones: Yemen as an example. Journal of Global Health, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.7189/JOGH.10.010375

29. Looi, M. K. (2020). Covid-19: Deaths in Yemen are five times global average as healthcare collapses. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 370, m2997. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2997

30. Save the Children. (2020). Yemen: Deaths Due to COVID-like Symptoms Surge in Aden as Hospitals Close. Save the Children 2020 Press Releases. https://www.savethechildren.org/us/about-us/media-and-news/2020-press-releases/deaths-due-to-covid-like-symptoms-surge-in-yemen

31. Bin Gouth, A., Bahashem, Y. A., & Alsheikh, G. M. (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic and Endemic Febrile Illnesses: The Dilemma of Exclusion and Diagnosis with Limited Capacities in Aden, Yemen. Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing. https://doi.org/10.7176/jhmn/77-01

32. Koum Besson, E., Norris, A., Ghouth, A. S. B., Freemantle, T., Alhaffar, M., Vazquez, Y., Reeve, C., Curran, P. J., & Checchi, F. (2021). Excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic: A geospatial and statistical analysis in Aden governorate, Yemen. BMJ Global Health, 6(3), 4564. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004564